Much of the supporting cast of Threads were people from the Sheffield area

One of the most terrifying programmes ever shown on British television, Threads is the nuclear apocalypse drama-documentary that continues to haunt people’s nightmares 40 years on. Ahead of a rare new showing on the BBC, here’s a look at how the drama still has the potential to terrify people.

First broadcast on 23 September 1984, anyone who tuned in to BBC Two on that Sunday evening would experience a bleak and unforgettable depiction of a massive nuclear bomb attack on a British city and its aftermath.

It was a nightmare scenario that was all too plausible in an era of heightened tension between the West and the then Soviet Union.

Rarely seen on television since its first broadcast, it's being shown again on BBC Four and iPlayer on 9 October.

Sheffield was chosen as the fictional nuclear target because its writer, Kes author Barry Hines, lived there.

Ahead of transmission, about 600 people from the area who volunteered to work as extras were invited to a private viewing of the film. Some were involved with amateur dramatics while others just thought it might be a bit of fun. Maybe they could spot themselves or their friends on television.

No one was expecting anything quite like this.

1984: Look North interviews some of the extras who have just watched Threads

One young woman told the BBC’s Look North news programme: “When I was doing it, it was just a good laugh, you know? I didn't really think about what it would likely be like to see it, and when you see it it's a lot different - it's very disturbing.”

Another woman, trying to hold back tears, said: “I didn't think I would have reacted like this but I just couldn't help it. There's just going to be nothing after, is there? Nothing.”

Named Threads because of the strands that bind life together in a large city, it covered the events leading up to the attack and the 13 horrendous years after it, as seen through the lives of two families, the Kemps and the Becketts.

Their attempts to survive after the attack make for harrowing viewing, with society breaking down as nuclear winter sets in.

Another woman who appeared as an extra said that while she was watching the drama she thought “everybody's going to get out of it like all the other films,” but Threads offered no hope.

“I want to die when it hits me because I don't want to live through anything they lived through, not at all - it was horrible,” she added.

The effect of a nuclear attack on Sheffield was calculated precisely by the makers of Threads, whose director Mick Jackson had previously worked on the grim 1982 BBC documentary, QED: A Guide to Armageddon.

Such a one-megaton airburst would create shockwaves causing severe damage to buildings up to nine miles away.

Much of the following morning’s Breakfast Time was given over to discussing the issues raised by the programme.

Showing impeccable timing, Boy George was on as a guest to promote Culture Club’s new single The War Song, with its catchy “war is stupid” chorus.

He said: “A lot of people see war programmes as something really glamorous, so I think it’s about time they did see things that show it for what it is."

Threads extras Norma and Debbie Neath talk about the experience on Breakfast Time

Breakfast Time reporter Paul Burden spoke to another two women who signed up as extras, only to receive “a brutal first-hand lesson in the realities of life after the bomb”.

For Norma Neath and her daughter Debbie who lived on the outskirts of Sheffield in the village of Coal Aston, in the event of such an attack “the chance of instant death would be only one in 20”.

Debbie said on the day of filming, it started off as a laugh but by the end “it became a bit too real”.

She said: “They'd got all people laid out with horrible wounds and nasty things, and we were freezing cold and beginning to feel how we probably would really feel if we were in that situation.”

Writer Barry Hines said it was not their intention merely to shock “like it was a horror film”.

“It's just that it's such a shocking subject that there's some very harrowing scenes in it, and so there's no way that we could avoid shocking the audience,” he said.

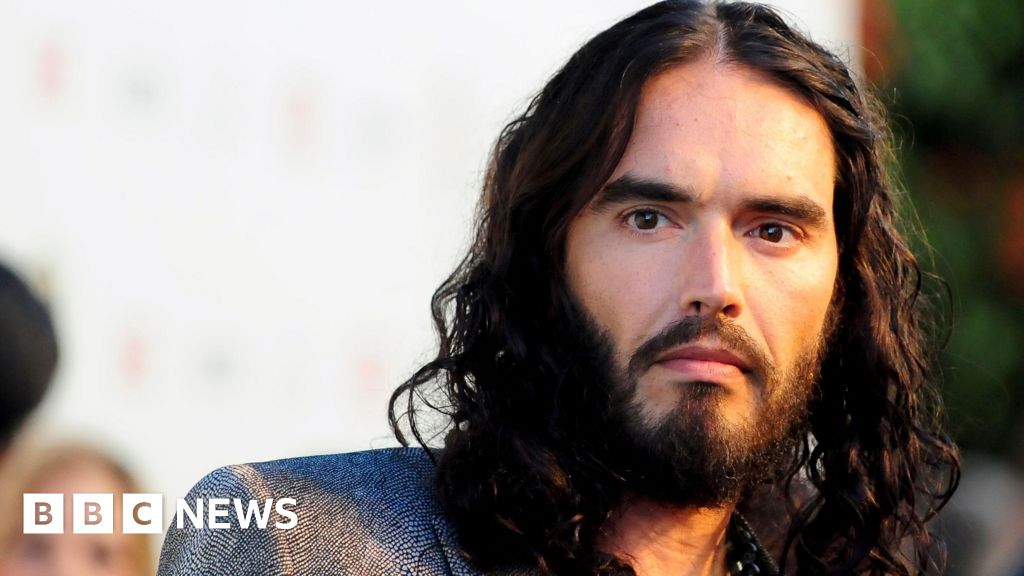

Karen Meagher and Reece Dinsdale played the young couple at the centre of the family drama before the bomb dropped

Threads creators Barry Hines and Mick Jackson explain why they tackled the subject in this way, on Pebble Mill at One

On the day after the Threads broadcast, Hines and Jackson also appeared on Pebble Mill at One to deliver a sobering message for viewers of the cosy lunchtime magazine programme.

Hines said his main reason for making Threads was to get people thinking about nuclear weapons, as “a lot of people don’t know anything about it”.

Jackson said many people had the “misconception” that a nuclear bomb meant “a flash and a bang and it's all over”.

He added: “I think Threads might have shown those people that in fact, in even the severest worst scenario for a nuclear war that you can imagine, more people are going to survive than perish immediately, and that sort of long, drawn-out suffering is something that most people would have to go through if it happens.”

Journalist John Tusa introduces the broadcast of Threads on BBC Two

Later on, Newsnight was given over to a special debate featuring a panel of military and strategic experts from Britain and the US, along with representatives from the three main parties.

Three questions were under discussion:

Can nuclear escalation be controlled so that it stops well short of mass destruction and the nuclear winter?

What lessons can be drawn about Britain's civil defence programme and its ability to provide either for the aftermath of a mass nuclear attack or the prospect of nuclear winter?

What effect does the nuclear winter hypothesis have on nuclear deterrence and our readiness to rely on nuclear weapons as a key element of defence?

Threads has since become cult viewing, although it has been rarely broadcast on the BBC in the following 40 years.

Director Mick Jackson will introduce a fresh showing on BBC Four and BBC iPlayer, at 22:00 BST on 9 October.

At the time, television critics largely approved of the decision to show Threads.

Herbert Kretzmer of the Daily Mail said that recent programmes about nuclear weapons had showed the BBC “confidently fulfilling its ancient role as a convener and focus of national debate”.

But he worried about the film's purpose. “Is there not a sense in which programmes like this, while seeking to alert the populace, succeed mainly in paralysing the will?”

In the Times, Peter Ackroyd commented: “It was not clear if the point of Threads was to frighten or inform... they are not incompatible aims, although I suspect they come under the larger heading of entertainment.”

Sean French in the Sunday Times wrote: “By the end we were a little better informed and a lot more worried. Answers were as far away as ever.”

Experts and interested parties give their reaction to Threads, on Did You See

A week after Threads was broadcast, the television review programme Did You See sought a range of views from people with a professional interest in the subject.

Bruce Kent of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament felt that "at the end it could have given people a bit more positive direction about the sorts of things they could actually do".

Military strategist Air Vice-Marshall Stewart Menaul remained sceptical about the programme’s claims.

He said: “Let me emphasise straight away, nobody is going to start chucking 5,000 megatons around this planet. Nobody, neither the Russians, the Americans, the British, the French, or anybody else. It will simply never happen.”

One of those who watched the film at a formative age was Black Mirror writer Charlie Brooker, who was 13 in 1984.

He told Desert Island Discs in 2018: “I remember watching Threads and not being able to process what that meant; not understanding how society kept going."

He added: "I assumed it [nuclear war] was going to happen and I think in the 1980s it did seem like that was going to happen."

While the world has changed in so many ways since Threads was first broadcast, it retains its harrowing power.

Movie

Movie 3 months ago

79

3 months ago

79

![Presidents Day Weekend Car Sales [2021 Edition] Presidents Day Weekend Car Sales [2021 Edition]](https://www.findthebestcarprice.com/wp-content/uploads/Presidents-Day-Weekend-car-sales.jpg)

English (United States)

English (United States)