BBC / Getty Images

BBC / Getty Images

Burning household rubbish in giant incinerators to make electricity is now the dirtiest way the UK generates power, BBC analysis has found.

Nearly half of the rubbish produced in UK homes, including increasing amounts of plastic, is now being incinerated. Scientists warn it is a “disaster for the climate” - and some are calling for a ban on new incinerators.

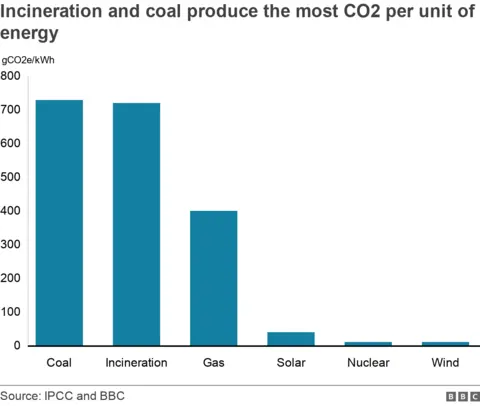

The BBC examined five years of data from across the country, and found that burning waste produces the same amount of greenhouse gases for each unit of energy as coal power, which was abandoned by the UK last month.

The Environmental Services Association, which represents waste firms, contested our findings and said emissions from dealing with waste are “challenging to avoid”.

Nearly 15 years ago, the government became seriously concerned with the gases being produced from throwing away household rubbish in landfill and their contribution to climate change. In response, it hiked the taxes UK councils paid for burying waste.

Facing massive bills, councils turned to energy-from-waste plants - a type of incinerator that produces electricity from burning rubbish. The number of incinerators surged - in the past five years the number in England alone has risen from 38 to 52.

These incinerators were described by the waste disposal industry as a green alternative to landfill.

This is certainly the case for food waste, which produces less harmful greenhouse gases when burned, but it is not the case for plastic waste. Plastic is made of fossil fuels and burning it, rather than burying it in landfill, produces high levels of greenhouse gases.

In the past few years, more plastic has been going to incinerators and less food waste - which councils are now sending to anaerobic digesters or to be composted. But the government’s own calculations continue to assume that we send the same mix of rubbish as we did back in 2017 - potentially underestimating the scale of the issue.

The BBC’s five-year analysis used data on actual pollution levels recorded by operators at their incinerators, and found that energy-from-waste plants are now producing the same amount of greenhouse gases per unit of electricity as if they were burning coal.

For the past three decades, the UK has been reducing its use of coal because of how polluting it is - and last month closed its last coal plant. The government hopes this will help it achieve its target of ensuring electricity generation produces no carbon emissions by 2030.

This now leaves waste incineration as the dirtiest way the UK produces power. According to the BBC analysis, energy produced from waste is five times more polluting than the average UK unit of electricity.

About 3.1% of the UK’s energy comes from waste incinerators - but the government’s independent advisory group, the UK Climate Change Committee, warns that incineration will make up an increasing part of emissions from electricity generation.

It’s an “insane situation”, said Dr Ian Williams, professor of applied environmental science at the University of Southampton.

“The current practice of the burning of waste for energy and building more and more incinerators for this purpose is at odds with our desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.

“Increasing its use is disastrous for our climate.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Nearly half the UK's household waste now goes to incinerators

Lord Deben, the Conservative environment minister who introduced the landfill tax in 1996, told the BBC: “We’ve got too many [incinerators], and we shouldn’t have any more… they begin to distort our ability to recycle.”

And yet, incinerators are still being built in England. The UK government approved a new £150m site in Dorset last month, overturning the local council’s decision to block it.

Dorset Council leader Nick Ireland told the BBC at the time that it "kneecaps" the county’s efforts to achieve their "net zero" target - the goal of no longer adding to carbon emissions by 2050.

In the past few years, Wales and Scotland have introduced bans on new incinerator plants over environmental concerns, and there have been increasing calls from leading academics and environmental groups for the same to happen in England and Northern Ireland.

These include the UK Climate Change Committee, which has recommended that no more plants be built without efforts to capture all their carbon emissions.

There are currently only four out of 58 incinerators in the UK with approved plans to capture their emissions and one pilot project that is operating. This project at Ferrybridge EfW collects one tonne of carbon dioxide annually - but the site produces more than half a million tonnes of CO2.

Incinerators getting dirtier and bigger

Without action, it is expected that the use of incinerators in the UK will continue to grow and they will probably get more polluting.

There are currently dozens of new plants going through the planning process, and existing ones are growing in capacity. The BBC investigation found nearly half of all incinerators in the UK have managed to get a capacity increase approved by the Environment Agency without applying for a new permit - which requires public consultation.

The waste they are burning is increasingly made up of plastic, according to local government data. Because plastic is produced from fossil fuels, it is the dirtiest type of waste to burn.

According to the government’s own statistics, burning plastic produces 175 times more carbon dioxide (CO2) than burying it in landfill.

Prof Keith Bell, who sits on the UK Climate Change Committee, said after reviewing the BBC's findings: “If the current government is serious about clean power by 2030 then... we cannot allow ourselves to be locked into just burning waste.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

Increasing amounts of plastic waste are making incineration more polluting

In April, a temporary ban on permits for new incinerators was introduced in England by the previous Conservative government, while it reviewed the role of burning waste, but when the ban lapsed in May it was not continued.

It appears that the current government has yet to decide its position on the issue.

In a letter last month, senior civil servants at the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said they were unable to decide whether to approve a proposed incinerator in North Lincolnshire until the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) had decided the government’s policy on burning waste for power.

Considering the Dorset incinerator was approved by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, this letter raises questions about the consistency of the government’s approach on this issue.

In response to a request for comment, a Defra spokesperson said: “We are considering the role waste incineration will play as we decarbonise and grow the economy.”

Councils ‘locked in’ to burning waste

The challenge is that even if local authorities wanted to move away from the use of energy-from-waste plants they are often unable to due to restrictive, long-term contracts.

The BBC made Freedom of Information requests to every UK local authority responsible for disposing of waste, which revealed that they have at least £30bn-worth of contracts with waste operators involving incinerators, some lasting more than 20 years.

These arrangements have been criticised by the House of Commons public accounts committee for locking councils into financially burdensome arrangements.

Dr Colin Church, who led an independent review of incineration for the Scottish government which resulted in the ban, said: “‘Lock-in’ is a real issue, the energy-from-waste sector swears blind it’s not, but it is.”

In 2019, Derbyshire County Council and Derby City Council terminated their contract with waste company RRS because an incinerator it had built for them did not pass initial tests, with residents complaining about the smell and noise.

Although the plant had never been used, the councils were were ordered to pay £93.5m in compensation to RRS’s administrators for terminating the contract early.

The BBC also found that dozens of councils had clauses in their contracts which demand a minimum amount of waste to be sent to incinerators for burning - known in the industry as “deliver or pay”.

In 2010, Stoke-on-Trent Council was left facing a £329,000 claim from Hanford Waste Services for not sending enough waste to be incinerated.

The council declined to say if it paid the claim but told us the clause has since been removed from its contracts with the operator.

BBC / Jon Parker Lee

BBC / Jon Parker Lee

Local authorities have more than £30bn of contracts involving incinerators, some lasting more than 20 years

But the Local Government Association (LGA) - representing local authorities in England and Wales - expressed concerns to the BBC that these contracts have left councils unable to explore the use of more environmental solutions, such as recycling, for fear of a fine for breach of contract.

Joe Harris, vice chair of the LGA and leader of Cotswold District Council, said: “If we can adapt those contracts which allows us to reduce the amount of waste going to incineration and if we can boost recycling we want to do that, but we can’t have councils facing financial penalties.”

For the past 10 years recycling rates have failed to increase, remaining stuck at about 41% in England - despite a previous commitment by the previous Conservative government for 65% of the UK’s household waste to be recycled by 2035. Wales is the only nation to have hit the 65% target.

But the Environmental Services Association, the waste industry body, said burning rubbish for energy has been “complementary to efforts to recycle more” over the past decade and that “stagnant recycling rates are only indicative of a failure to develop recycling policies”.

A Defra spokesperson told the BBC: “We are committed to cutting waste and moving to a circular economy so that we re-use, reduce and recycle more resources and help meet our emissions targets.”

How we calculated the emissions

In order to calculate the emissions produced per unit of energy from England’s incinerators, the BBC needed to obtain the emissions produced and the power output from these sites.

Each incinerator in the UK produces annual monitoring reports, which record key statistics associated with the plant including its total emissions.

But in a few cases the emissions were not recorded in the annual monitoring report and so the figures recorded in the government’s pollution inventory report were used.

The IPCC, the UN climate science body, recommends that “biogenic” emissions - which come from burning organic matter like food - are not included in calculations because they are recorded under the emissions for the land and forestry sector.

Some operators recorded this, but in the cases where they did not the government guidelines

This gave the BBC the total fossil emissions - meaning those associated with burning the “fossil” waste (or non-organic waste) at the site, including plastic.

Then we calculated a carbon intensity figure - the carbon emissions per unit of energy generated - for every site, by dividing the total fossil emissions by the energy generated.

Methodological support was provided by Francesco Pomponi, professor of sustainability science at Edinburgh Napier University; Massimiliano Materazzi, associate professor of chemical engineering at University College London; and Dr Jim Hart, sustainability consultant.

Movie

Movie 2 months ago

67

2 months ago

67

![Presidents Day Weekend Car Sales [2021 Edition] Presidents Day Weekend Car Sales [2021 Edition]](https://www.findthebestcarprice.com/wp-content/uploads/Presidents-Day-Weekend-car-sales.jpg)

English (United States)

English (United States)